There are approximately 10,000 people on the UK transplant list waiting to receive an organ. Statistics show that, due to a shortage in organs available for transplant, every day 3 of these people will die before receiving their transplant. Unfortunately, we have not yet found a way to address this shortage. However, with this in mind, money is being poured into investigating new technologies aimed at tackling this problem.

But how? Well, the answer may have been under our noses all along. Using a popular everyday technology, we may be able to use printing with a modern twist to generate these desperately needed organs. Imagine being able to print out a new liver, or a lung, or in fact whatever organ you needed.

In 2011 Dr. Anthony Atala, director at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, received a standing ovation when, on stage during a presentation, he printed out a prototype kidney made from living cells. Although far from perfect, the kidney was able to break down toxins and produce a waste-like product, just like the genuine thing. Despite their diminutive size, these ‘miracle organs’ have the potential to revolutionise medicine as we know it.

In 2011 Dr. Anthony Atala, director at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, received a standing ovation when, on stage during a presentation, he printed out a prototype kidney made from living cells. Although far from perfect, the kidney was able to break down toxins and produce a waste-like product, just like the genuine thing. Despite their diminutive size, these ‘miracle organs’ have the potential to revolutionise medicine as we know it.

And these aren’t the only organs to have been produced using 3D printing. Scientists at Organovo, a bioprinting specialist, have now created miniature livers. These tiny livers are just 4mm wide and ½ mm in depth, but are still able to produce the proteins essential for carrying hormones and drugs. Importantly, the livers produce cytochrome p450, which is vital for breaking down drugs in the body. What’s more, cells from blood vessels can be incorporated into the livers to supply them with oxygen and other nutrients.

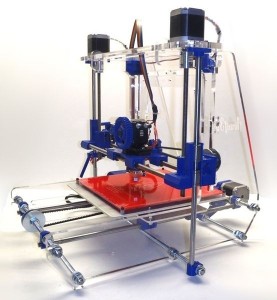

3D printers work by printing out layer upon layer of ink (or any other substance) until a 3D object is achieved. All we have to do is tell the printer what to print with a computer aided design program, hit the print button and let the magic commence. Hey presto- there you have a real-life 3D object.

3D printers work by printing out layer upon layer of ink (or any other substance) until a 3D object is achieved. All we have to do is tell the printer what to print with a computer aided design program, hit the print button and let the magic commence. Hey presto- there you have a real-life 3D object.

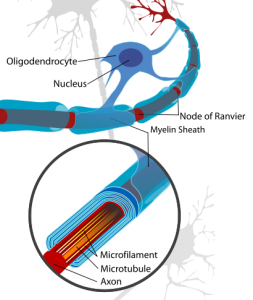

When printing organs, layers of living cells are laid out in sheets upon each other and a scaffolding material called hydrogel is spread between the layers providing nutrition to the cells and helping them fuse together. The cells are able to survive for as long as four months in these conditions. Images of the patient’s original organs are generated using a CT scan which forms a template that instructs the printer on how to to produce a life-like replica of the organ.

Although 3D printing may seem ultramodern, it has actually been used in the medical field some time to produce things such as hearing aids and braces. This technology has astonishingly also been used to create an entire lower jaw for an elderly women who was deemed too fragile to undergo reconstructive surgery. The jaw was designed to be realistic, with cavities and grooves in the mould to allow for the re-attachment of jaw muscles and nerves.

We are now at a stage where we are able to print sheets of living cells, but only on a small scale. Researchers have surmounted a massive hill, and have finally found a way to pass human embryonic stem cells through a 3D printer without sustaining any significant damage to the cells.

Researchers are hopeful that over the next few years we will be able to use these tissue strips to test the toxicity of new drugs before exposing living patients to these potentially dangerous substances, saving not only time and money but also reducing risks to patients. Using the so-called mini organs, researchers will be able to watch the progression of diseases in life-like organs outside of the body.

Over the course of the next 10 years we will most likely see 3D printing being used to assist in regeneration such as bone and skin grafts, patches for heart conditions, regeneration of sections of blood vessels and replacement cartilage for joints.

As for producing entire organs, there is still a long way left to go. The problem lies with being able to produce a fully functioning organ on a full-size scale with the ability to maintain its own oxygen supply via a vascular system, and to remove its own waste. The hope is that researchers will be able to devise a way that will allow a printer to produce a full scale organ without any damage to the cells, and that is sufficiently supplied with oxygen and nutrients. If we manage to achieve this, then using ‘printed’ organs may cease to be something of a dream and become a reality. Over the next 10 or 20 years, the thousands of people likely to need a transplant could be lucky enough to receive an organ almost immediately instead of waiting months or even years as is the case now.

Post by: Sam Lawrence

For more information on organ donation or to join the organ donor register visit: http://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/

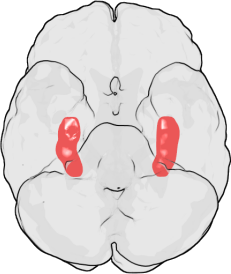

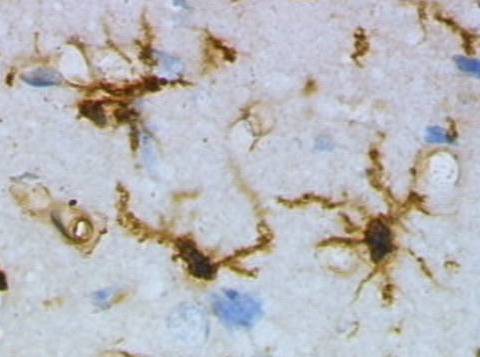

Resting (top) and activated (bottom) rat microglia after a brain injury. Images by Grzegorz Wicher (Wikicommons).

Resting (top) and activated (bottom) rat microglia after a brain injury. Images by Grzegorz Wicher (Wikicommons).