Almost three quarters of the British population participate in gambling of some form, despite the fact that we know the odds are so heavily stacked against us. So why do we gamble despite the massive risk?

The answer to this question lies in the biology of our brains; exactly how does the brain change during addiction? Circuits known as the ‘reward system’ connect to regions of the brain involved in memory, pleasure and motivation. When we enjoy something these neurons release dopamine, a chemical neurotransmitter that makes us feel happy, a feel-good chemical that makes us satisfied and encourages us to continue our habits. This is similar to what happens in the brains of drug addicts.

A collaboration between Drs Luke Clark from the University of Cambridge and Henrietta Bowden-Jones from the only NHS clinic for gambling addicts is trying to address what makes some of us so hooked on gambling and what happens in our brains. We know that there are both external and internal factors that influence our gambling habits such as our personality type, neurobiological and neurochemical make-up, as well as the different features of the games themselves.

Using a number of control and ‘gambler’ subjects, behavioural tests looked at impulsivity, compulsivity and dopamine levels. As suspected, gamblers were more impulsive than controls; something which is mirrored in drug addicts and alcoholics. Brain imaging studies have shown that near-misses recruit areas of the brain that are associated with winning. The ‘near-miss’ phenomenon is the theory that losing a game acts as an aversive stimulus- it actually puts us off gambling. But, coming close to winning acts to fuel our desire to gamble. The fact that the same areas are activated when we almost win, and when we actually do win may encourage us to gamble – and this is something that can be exploited by game manufacturers.

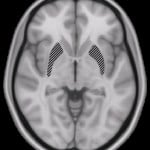

Is the degree of brain activation during winning related to gambling severity? Subjects were asked to play on a slot machine whilst an fMRI machine measured brain activity in response to the game (functional magnetic resonance imaging- looking at the level of blood flow to areas of the brain in response to stimuli). Results found that those subjects with severe gambling addictions had the greatest activity in their midbrain in response to near-misses, but the activity to a real-win did not differ with gambling severity. This brain region is of interest because dopamine is produced here, and is implicated in other addictive behaviours such as alcoholism.

This leads us to ask if there is a chemical basis to gambling addiction. Well, scientists know that there are a decreased number of dopamine receptors in the brains of drug addicts, but is this mirrored in the brains of gambling addicts? Surprisingly, although there were no differences overall in the amount of dopamine receptors in gamblers compared to controls, gamblers that were more impulsive did have a lower number of dopamine receptors. Strikingly, when they studied the gambling behaviour of patients who had suffered a brain injury, the ‘near-miss’ response observed in gambling addicts was not seen in patients that had damage to their insula. The insula may be central to the distorted thinking patterns seen in gamblers.

Compulsive gamblers are not necessarily greedier than the rest of us, but their brains may be wired differently. Gamblers are more likely to prioritise money over other basic needs such as food and social interactions. Perhaps there are changes in a gamblers brain that render them hyper-sensitive to the ‘rush’ of winning. On the flip-side, it is possible that pathological gamblers are less sensitive to the things that the rest of us would find rewarding, such as alcohol or sex.

Healthy controls and pathological gamblers were put into an fMRI scanner to record brain activity during a task where they had to press a button in response to money-based or sexual images. The faster the button was pressed, the more motivated the subject was to get the reward. Despite stating that they found both money and sex equally rewarding, results found that gamblers pressed the button 4% faster when viewing money-related images than sexual images. Indicating that gamblers attributed a higher value to money than sex. The gambling cohort had increased blood flow to the ventral striatum (part of the brain involved in reward processing) in response to monetary images, more than to sex. In contrast, no difference was found in the controls. Interestingly, they found altered activity in the orbito-frontal cortex of gamblers, which is also involved in reward processing. Past studies have shown that different parts of the orbito-frontal cortex are activated in healthy individuals in response to money and erotic images- which is thought to reflect the dissociation between rewards that are vital to survival such as food and sex, and secondary rewards such as money and power. In gambling addicts, the same region of the orbito-frontal cortex was activated in response to sex and money, suggesting that they have an altered perception of money as a more primal reward.

A large proportion of future work will focus on uncovering the precise role of the insula in addiction by observing how its activity changes whilst gambling. Another area of interest is looking at relatives of gambling addicts, and trying to identify if differences exist in both their brain activity and also in their behaviours when gambling. This may be of huge importance as therapies and treatments may be able to focus on targeting affected areas of gamblers’ brains.

For more information:

Clark L, Lawrence AJ, Astley-Jones F, Gray N. Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron. 2009; 61(3):481-90.

Sescousse G, Barbalat G, Domenech P, Dreher JC. Imbalance in the sensitivity to different types of rewards in pathological gambling. Brain. 2013

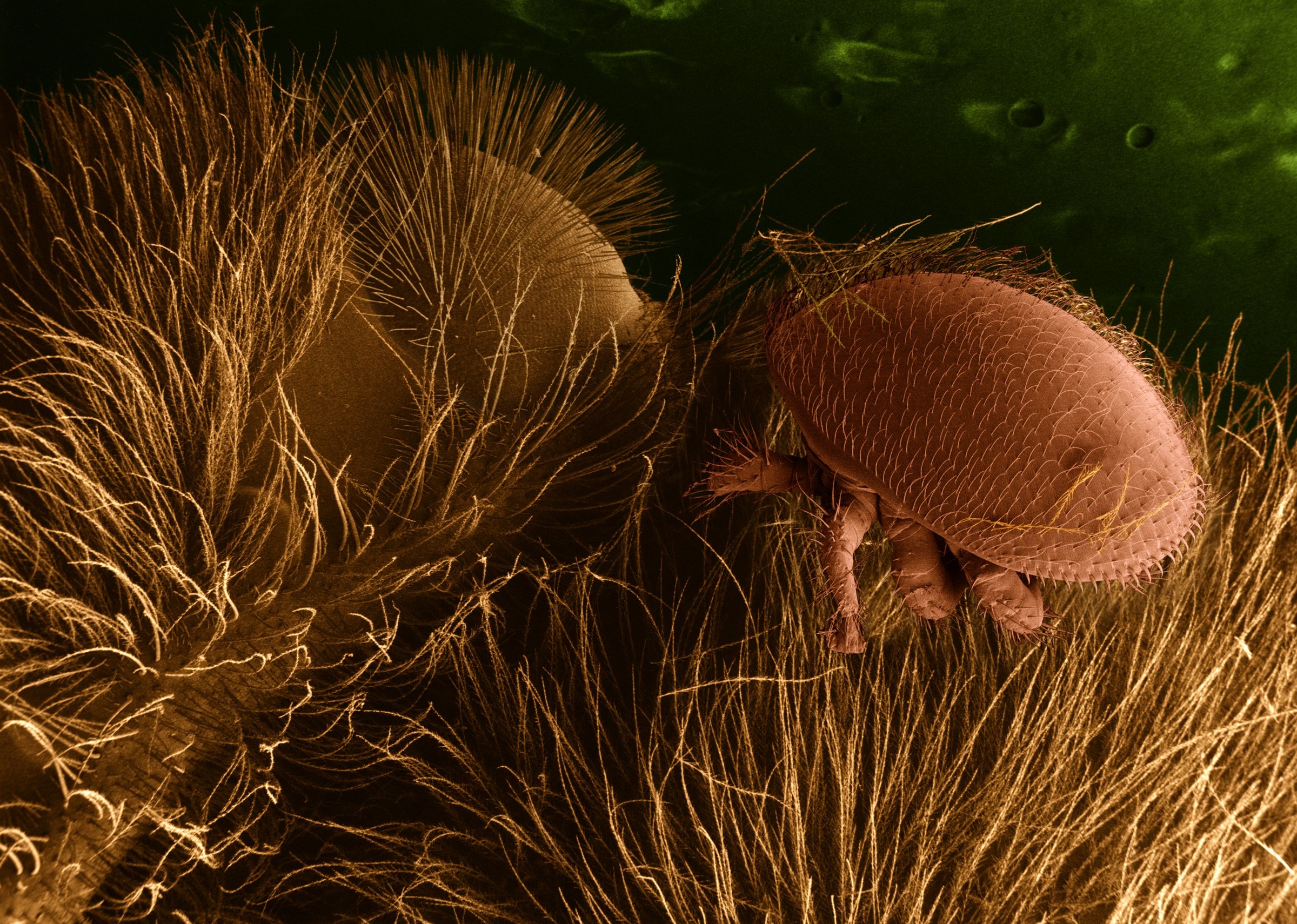

Image taken from Ted Murphy, Flikr

Post by Samantha Lawrence