Seven times Formula 1 World Champion and holder of a huge number of driving records, Michael Schumacher is thought of as the greatest F1 driver of all time, a champion among champions. On 29th December last year on a ski slope in the French Alps, Schumacher fell and hit his head on a jagged rock. Witness reports claim that he lost consciousness for about a minute, but that ten minutes later, when the emergency helicopter arrived, he was conscious and alert. Over the next two hours, however, Schumacher’s condition deteriorated and since that day, he has had two head operations and has remained in intensive care under a medically-induced coma.

Traumatic brain injury, or TBI, is quite a vague medical term and simply describes any injury to the brain sustained by a trauma – that is, a serious whack to the head. TBI is the most common brain disorder in young people: while older people are at higher risk from degenerative diseases, young people are more likely to find themselves in car crashes, fights or…ski accidents.

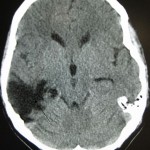

The specific type of TBI that Schumacher is believed to have suffered is an epidural haemotoma (click here for a seriously gory video of a haemotoma clot removal – you have been warned). Between the brain and the skull are a number of protective layers; these are membranes which encapsulate the brain and spinal cord, all of which swim around in cerebrospinal fluid. An epidural haemotoma is a bleed between the tough outermost membrane, called the dura mater, and the skull. Technically this sort of bleed isn’t in the brain itself, but this injury seriously affects the brain due to one important factor: pressure.

Since the skull is an almost totally enclosed space, a bleed that grows too big in size could end up pushing, not just on the inside of the skull, but on the brain itself – squeezing it into an ever-decreasing volume. When put under pressure the only way the brain can physically go is down towards the spinal cord, but if this happens, the brainstem at the base of the brain may become compressed. This horrible scenario, known as ‘coning’, has a really high fatality rate, as the brainstem is needed to keep our heart pumping and lungs breathing. So keeping intracranial (in-skull) pressure low after TBI is key.

Doctors have reported that, as well as a haemotoma, Schumacher suffered contusion and oedema. Cerebral contusion is essentially bruising, as you might expect in other parts of the body: tiny blood vessels bleed when they have suffered a serious hit – in this case either from the rock itself, or from the other side of Schumacher’s skull in a ‘rebound’ type impact. Oedema, or swelling, may come as a result of the contusion – like when a bruised knee swells – and again would need to be curbed in order to prevent the pressure inside the skull from rising dangerously.

So what have the doctors done to treat Michael Schumacher’s condition? Well, firstly, the surgeon Prof. Stephan Chabardes has reportedly performed two operations to remove blood clots from the haemotoma, as well as a craniectomy – removal of part of the skull – in order to relieve the intracranial pressure and prevent coning. Craniectomy has been used for some time to treat both TBI and stroke, but remains somewhat controversial, mainly because of the risks of further bleeds, infections, or herniation of brain tissue through the surgically-made hole in the skull.

The second main strategy in treating Michael Schumacher has been to keep him under an artificial or medically-induced coma. This involves sedating him with strong anaesthetic agents. Propofol, which quietens brain activity by boosting inhibitory GABAA (‘off’) receptor activity and by blocking sodium (‘on’) ion channels in neurons, or barbiturates, which also enhance GABAA receptors, but block excitatory glutamate (‘on’) channels could be used to keep him sedated and to ‘slow’ his brain down. Slowing is achieved through a net reduction in excitatory activity within the brain. Thus, the medically-induced coma not only stops the patient being conscious, through what no doubt would be a painful experience, but also limits the amount of activity-related blood flow, curbs swelling and prevents what’s known as excitotoxicity.

Excitotoxicity can occur after TBI, stroke or in patients with epilepsy. It is a term used to describe what happens when brain cells run out of energy or become overloaded with excitatory inputs. In this state cells become overexcited and die, either immediately, or after a delay. Seizures, which can cause excitotoxic cell death, are fairly common after severe TBI and are thought to drive brain damage after the original injury. Seizures after TBI can be worsened by swelling and higher temperatures, so it is likely that Schumacher has been kept a few degrees cooler than his normal body temperature to limit this risk.

If he is still in a medically-induced coma, or is gradually being weaned off the anaesthetic agents, Schumacher may be undergoing physical therapy to move his limbs and joints to prevent muscle wastage, or contracture, which is irreversible muscle shortening. If his condition improves and he is able to move, his limbs will need re-strengthening.

Some conflicting reports suggest that doctors treating Michael Schumacher may have started removing him from his coma. If they are doing this, the full extent of their patient’s rehabilitation needs won’t become clear for some time. While I obviously hope the driving legend makes a full and speedy recovery, it is hugely unlikely that his brain will completely recover all its previous functions. The brain is such a delicate organ and Schumacher’s tragic case only highlights its fragility.

Schumacher’s injuries also raise the debate on the guidelines of treating head injuries in sports. Last November, Tottenham’s Hugo Lloris lost consciousness after a hit to his head during a football match, but after waking up was allowed to return to the pitch to finish the game. Lucid intervals, such as the one reported shortly after Schumacher’s fall, can be deceptive and players of contact sports should always be given immediate medical attention after losing consciousness. It’s no news that the cumulative effects on the brain of losing consciousness multiple times – as many boxers do on a regular basis – are to be avoided at all costs.

Every year in the USA, 1.7 million TBIs – more than double the number of heart attacks – contribute to almost a third of all accidental deaths as well as varying levels of lasting disability. While we hold our fingers crossed for Michael Schumacher’s successful rehabilitation, we must also think of the other thousands of people, and their families dealing with the long-term aftermath of serious brain injuries around the world.

Post by Natasha Bray