In this post I will take a look at the moral and ethical dilemmas posed by de-extinction. I’ll address the issue from numerous angles; though I must admit that a post such as this cannot do more than scratch the surface of such a complex issue. What I hope it will do is spark some debate and encourage you to think about where you stand on the matter. This is an incredibly important field of research and one that warrants debate and discussion. As such, I’d invite you to leave a comment at the bottom of the page if you want to weigh in. So, here we go…

Morality

A key argument used to defend the theory of de-extinction is that it will allow humanity to atone for past mistakes. Most, if not all, of the species scientists are proposing to bring back went extinct because of human activities. If we can develop the ability to undo the damage we’ve caused then do we not have a moral obligation to do so?

Photo Credit: Bill Waller, via Wikipedia

Well, not necessarily! Just because we have the ability to do something doesn’t necessarily mean that we should. There have certainly been instances in which our ‘meddling’ with nature has had only positive results. For example, we wouldn’t have enough food had we not bred crops that grow at a faster rate and with greater yield. However, there have been many cases in which our attempts to improve our own lifestyle has dramatically backfired, as was the case when we tried to introduce the Cane Toad into Australia.

Photo Credit: Bart van Dorp, via Wikipedia

Linked into this matter is the horrendously complex question of how morally right de-extinction is as a concept. Mankind is just another species on the planet, naturally selected to achieve dominance in many environments. Therefore, one might argue that any tools and technologies we have developed are the result of our natural intelligence. Other species have learned to use rudimentary tools without us gasping in horror; for example, bearded capuchin monkeys use rocks to open nuts. If you follow this thought process logically you come to the conclusion that ‘de-extinction’ is just another natural application of our intelligence. But, of course, your viewpoint on this depends entirely on whether you set humanity apart from other species.

Conservation

The other major argument in favour of de-extinction is the fact that the techniques developed in pursuit of that end-goal could be used to help prevent endangered species going extinct in the first place. The biggest challenge in cloning an extinct species is getting the body of a living organism to accept an embryo containingmostly the extinct species’ DNA. If scientists can achieve this, then one could assume that they could do so with species that are not extinct, but endangered. We would then have a way of artificially boosting numbers of endangered species.

The counterpoint to this argument is that such an ability might encourage apathy. Leaving aside the question of our moral right to try and stop species going extinct, would we go to such great lengths to preserve endangered species if we knew we could just bring them back at a later date? Many people would argue that we wouldn’t and that, in trying to be more responsible for the world around us, we might become even less so.

Environmental Impact

Photo Credit: FunkMonk, via Wikipedia

Here we come to, in my opinion, the main crux of the argument. We have yet to consider how the revived species and the environment into which it is thrust will cope. For long-dead species, such as the woolly mammoth, the environment in which they lived will have changed drastically in their absence, adjusting to function without them. Regardless of whether they were wiped out by man, these species have lost their place in the world.

Let’s consider for a moment just a few of the ways in which the habitat of a species such as the woolly mammoth might have changed over time. Firstly, the climate may have changed. This could obviously mean that our de-extinct species can no longer survive in its old habitat. However, even if it could, if the average temperature or humidity has changed, then the range of other species that the environment supports could have changed drastically too. Animal species might have migrated or died off; plants might have died off or suddenly found themselves able to grow where they couldn’t before; and bacteria and viruses will doubtless have evolved massively over time too.

This leads onto the second major issue – the food web. If the inhabitants of the environment have changed in the absence of the extinct species, then it has no place in the modern-day food web. Quite frankly, even if the species living in an area haven’t changed, if enough time has passed then they will have evolved to survive without the extinct species, meaning it might still cause massive disruption. It might endanger the indigenous populations by outcompeting them or hunting them in a way they have not evolved to cope with, or it could be threatened with ‘re-extinction’ itself!

Finally, I mentioned earlier that bacteria and viruses would have evolved greatly over such a period of time. Well this offers no shortage of complications when trying to bring a species back from the dead. Obviously, a long-dead species’ immune system will be outdated, what with having missed out on potentially millennia of natural selection. We cannot know in advance but it might be that modern-day microbes could wipe out the resurrected species immediately if its immune system could not cope with these new threats.

Also, animals’bodies contain massive amounts of bacteria, which help our bodies to function. We could not digest our food as effectively as we do without bacterial colonisation. It is headache-inducing to try and work out the ways in which the body of a member of a resurrected species would respond to colonisation by all of these species that its ‘ancestors’ never encountered.

In short, it is very difficult to consider every single factor when introducing an organism into an environment in which it simply does not belong. There are often distant, subtle relationships and interactions between parts of an environment that we cannot anticipate.

Photo Credit: Enryū6473, via Wikipedia

In more extreme cases, scientists may try to make an environment suit the extinct species, rather than going about things the other way round. For example, the Siberian steppe that served as the woolly mammoth’s habitat changed drastically at the end of the Pleistocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years ago). Russian scientist Sergei Zimov has, since the 1980s, been reintroducing flora and fauna into an arctic region of Siberia dubbed ‘Pleistocene Park’ in a bid to recreate the ecosystem that was lost millennia ago. This could, ultimately, include providing a home for mammoths.

Of course, here, we’re talking about manipulating entire environments rather than individual species. It is difficult to know where to draw the line, if one even believes that a line should be drawn anywhere! In my opinion, the line should be drawn before even taking de-extinction beyond being just a theory. I don’t believe that the potential benefits of such an ability outweigh the incredible and unknowable risks that come with playing God in this manner.

As I said before though, I would be very interested to know what you think of this and if you would like to add to my list of arguments. Here, we really have only just begun to consider the ramifications and justifications behind this incredibly controversial area of research.

This  post, by author Ian Wilson, was kindly donated by the Scouse Science Alliance and the original text can be found here.

post, by author Ian Wilson, was kindly donated by the Scouse Science Alliance and the original text can be found here.

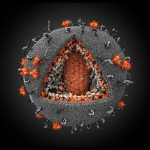

In 2010, a baby was born prematurely to a mother whose HIV was only discovered during delivery. With no prenatal care, and therefore a high risk of exposure to the virus, the gutsy call was made to begin aggressive treatment with a combination of three antiretroviral drugs at just 30 hours old. Infection was confirmed soon after and the child remained receiving therapy.

In 2010, a baby was born prematurely to a mother whose HIV was only discovered during delivery. With no prenatal care, and therefore a high risk of exposure to the virus, the gutsy call was made to begin aggressive treatment with a combination of three antiretroviral drugs at just 30 hours old. Infection was confirmed soon after and the child remained receiving therapy.