After being struck down with a particularly nasty chest infection, I initially put off going to see the doctor and instead opted for lots of rest, fluids and self-medication. After suffering at home for a few weeks with no alleviation of my symptoms, I eventually decided enough was enough and went to see the doctor. I was subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia and prescribed antibiotics to treat the infection, after which my symptoms finally began to ease.

After being struck down with a particularly nasty chest infection, I initially put off going to see the doctor and instead opted for lots of rest, fluids and self-medication. After suffering at home for a few weeks with no alleviation of my symptoms, I eventually decided enough was enough and went to see the doctor. I was subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia and prescribed antibiotics to treat the infection, after which my symptoms finally began to ease.

My reluctance to seek medical intervention was due in part to two reasons;

- My general dislike for going to the doctors

- Concern over recent news articles discussing the demise of the antibiotic due to over- prescribing.

It is the second of these reasons which seems to be a particular cause for concern.

The evolution of disease-causing bacteria, leading to antibiotic resistance, is a concern which has been high on the scientific agenda for decades. However, the media are only just starting to catch on to the stark reality that faces us. David Cameron has recently taken notice of this impeding issue, referring to the problem as ‘taking us back to the dark ages’. Cameron has called for a review into microbial resistance and has called for drug companies to invest in finding the next generation of antibiotics. But is this too little too late?

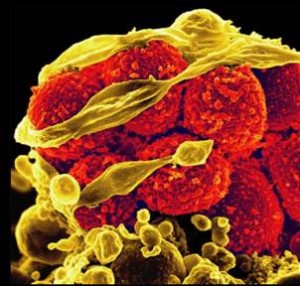

If our bodies become infected with foreign bacteria our internal immune system (white blood cells) act swiftly and efficiently to stop the spread of infection – usually before it has the chance cause noticeable symptoms. More often than not, our bodies are able to cope with such an attack without intervention. However, sometimes our bodies become overwhelmed and are unable to cope on their own – this is when we need to seek help from antibiotics.

Antibiotics have been relied on for the last 70 years and are vital in the treatment of bacterial infections (they are useless in the fight against viruses). These drugs work in one of two ways:

- By interfering with the bacterial cell wall or the contents within – a process which destroys the bacteria (bactericidal).

- By slowing down the growth of bacteria that can cause illness or disease (bacteriostatic). Thereby, ensuring that the bacteria is no longer able to multiply and infect us.

The development of antibiotics peaked in the 1950’s, after which there was a sharp decline in their development – no new classes of antibiotics have been developed since the ‘80’s! This is perhaps because there is not much money to be made from discovering new forms of antibiotics, so the pharmaceutical industry tend to focus on other, more lucrative, areas of research.

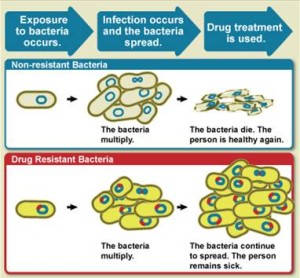

But how exactly does resistance to these drugs occur? When our bodies become infected with bacteria, there is a small chance that some of the bacterial cells show a natural resistance to antibiotics and therefore remain unaffected by the drug. This resistance could be due to a mutation that occurred by chance, or could be as a result of evolution – effectively the bacteria out-smarts the drug. These few remaining resistant bacteria survive, and rapidly reproduce so that the body becomes overwhelmed by this resistant strain. Drug resistance can then be transferred between bacteria through reproduction, physical connections between different cells and also through viruses called bacteriophages.

Antibiotic resistance is accelerated by over-use in the health-care and farming industries. Which is a growing concern, as many patients fight with doctors to be prescribed antibiotics for all minor ailments without considering the consequences of using them unnecessarily.

Antibiotics are also heavily used for intensive farming. With such a demand on farmers to produce lots of cheap meat, animals are housed in cramped conditions where infections are easily spread. Of course to prevent this spread, copious amounts of antibiotics are often used. This overuse facilitates resistance. Resistant bacteria are then able to spread from farm animals to people via our water supplies, which can then spread further from person to person by physical contact, coughing and sneezing.

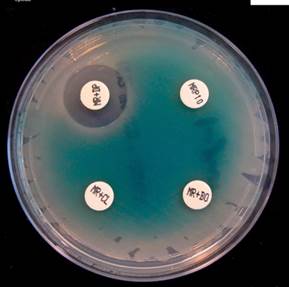

Now that we know the extent of the issue of antibiotic resistance, what can be done to tackle the problem both in the short and long term? Currently, drug-resistant superbugs such as MRSA and C.difficile cause 5,000 deaths a year in Britain. This has been controlled to some extent by implementing more stringent hygiene procedures in hospitals such as frequent hand washing and anti-bacterial hand scrubs. However, the occurrence of other resistant bacterial strains are on the rise; E.Coli cases have risen by two-thirds over the last few years.

In the short-term, a 5 year Anti-microbial Resistance Strategy has been put in place by the Department of Health which outlines a number of different points that are effective in the fight against antibiotic resistance;

Aim #1 To understand antibiotic resistance: to collect as much information as possible about the mechanisms that bacteria use to become resistant and to understand how the resistance spreads.

Aim #2 To conserve our current antibiotics: by improving hygiene in hospitals and by educating doctors and nurses about the issue of resistance, and encouraging them to only prescribe antibiotics when absolutely necessary.

Aim #3 To encourage the development of new antibiotics: by providing more incentives for pharmaceutical companies to invest in antibiotic development.

In terms of addressing antibiotic resistance in the long-term, several approaches can be taken. Firstly, we need to tackle the issue of over-prescribing. Currently, there are no diagnostic tests that allow doctors to determine whether infections are caused by bacteria or virus. So, developing a test that could determine the basis of aninfection would help doctors give the correct prescription. Secondly, drug companies need to create new classes of drugs to tackle bacterial infections. Thirdly, we can try to reduce the use of antibiotics in farming. Lastly more research needs to be conducted into a new innovative approach to tackling infections which uses viruses to treat bacterial infections.

A combination of over-prescribing and the lack of development of new antibiotics means that these drugs are rapidly becoming less effective in their fight against infections. There is the fear that, in the very near future, these drugs will cease working completely and simple things to treat such as cuts and flu will be likely to make us very ill and even cause deaths. With no suitable alternatives to antibiotics we could be looking at a very bleak future for medicine. With all of this in mind it is clear to see that the pharmaceutical and medical industry needs to make huge investments into developing new classes of antibiotics to fight these super-resistant bacteria. Alongside this, doctors need to be sure to prescribe these precious drugs sparingly and patients need to be careful not to rely on them so much for minor ailments.

Post by: Sam Lawrence