MS is one of the most common neurological disorder affecting young adults in the western hemisphere, indeed the list of sufferers include a number of high profile names.

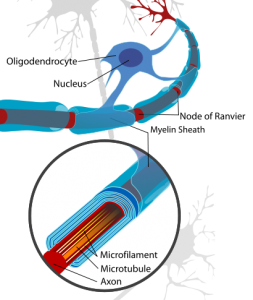

Although scientists are still unsure of exactly what causes the disorder, they do have a good working understanding of disease progression. Symptoms stem from damage to a fatty covering which surrounds nerve cells, known as a myelin sheath. It is this myelin which allows neurons to communicate quickly with one another through a process known as saltatory conduction. In brief, cells called oligodendrocytes (in the central nervous system) and Schwann cells (in the peripheral nervous system) reach out branching protrusions which wrap around segments of surrounding neuron forming a sheath (see image to the left). Signals traveling through myelinated neurons are able to move rapidly by ‘jumping’ between gaps in this sheathing known as nodes of Ranvier. In the case of MS, damage to this sheath causes signalling between neurons to slow down, leading to a range of symptoms.

Although scientists are still unsure of exactly what causes the disorder, they do have a good working understanding of disease progression. Symptoms stem from damage to a fatty covering which surrounds nerve cells, known as a myelin sheath. It is this myelin which allows neurons to communicate quickly with one another through a process known as saltatory conduction. In brief, cells called oligodendrocytes (in the central nervous system) and Schwann cells (in the peripheral nervous system) reach out branching protrusions which wrap around segments of surrounding neuron forming a sheath (see image to the left). Signals traveling through myelinated neurons are able to move rapidly by ‘jumping’ between gaps in this sheathing known as nodes of Ranvier. In the case of MS, damage to this sheath causes signalling between neurons to slow down, leading to a range of symptoms.

It is believed that, in the earliest stages of the disease, the body’s own immune cells (cells usually primed to seek out and destroy foreign agents within the body, such as viruses and parasites) mistake endogenous myelin for a foreign body and launch an attack.

Most current treatments focus on suppressing these immunological attacks by inhibiting the patients aberrant immune response. However, this novel and arguably ‘brutal’ new treatment focuses on destroying the patients existing immune system before re-building it again from scratch.

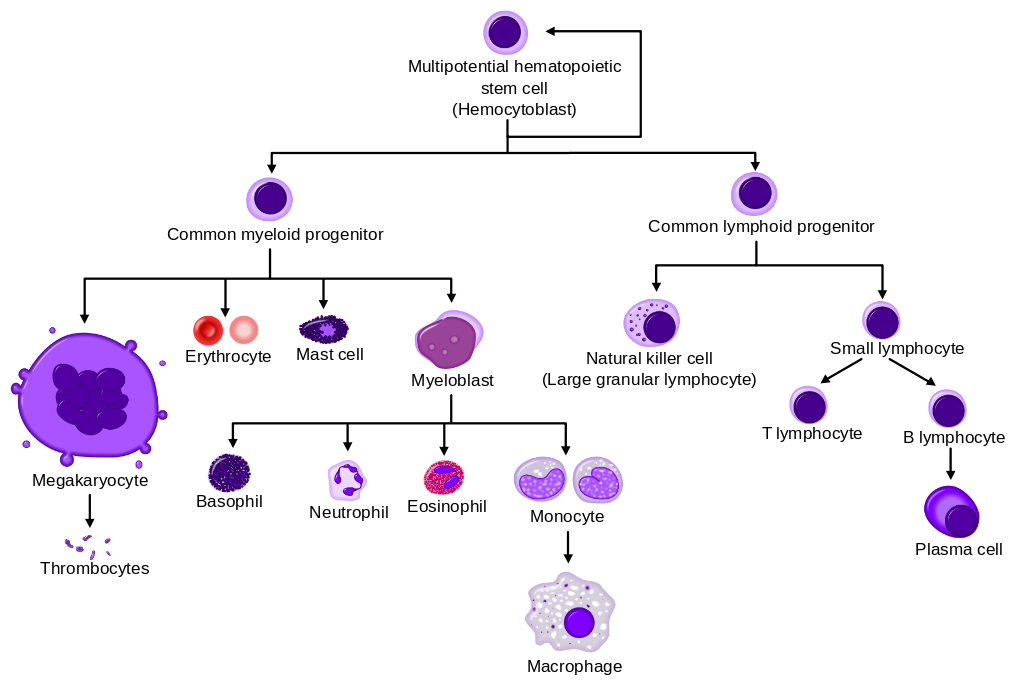

To understand how this treatment works, it is first necessary to give a bit of background into the immune system. Specialised immune cells, designed to protect our body from disease, are generated in our bone marrow. It is these cells which ‘misbehave’ in autoimmune diseases such as MS and can launch an attack our own cells. Key to this process is the existence of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) within the marrow. These cells are precursors to all other blood cells (including immune cells) and, given the correct environment, can develop into any other blood cell (see image below).

This new treatment requires three important steps:

First, it is necessary to harvest a number of these amazingly versatile HSCs from the patients and store them for later use. HSCs are either collected directly from a patients marrow through aspirations performed under general or regional anaesthesia or harvested directly from blood following procedures intended to enrich circulating blood with HSCs. Since HSCs make up only 0.01% of total the nucleated cells in bone marrow, these must be isolated from samples (based on either cell size and density or using antibody based selection methods) and purified before undergoing cryopreservation.

Next, the patient undergoes chemotherapy, with or without the addition of immune-depleting agents. The purpose of this is to eliminate disease in the patient, specifically by destroying the malfunctioning mature immune cells which are erroneously targeting and destroying healthy myelin. Since chemotherapy has a severe toxic effect and can cause damage to the heart, lungs and liver this procedure is currently limited to younger patients.

Finally, the cryopreserved HSCs removed in step one are reintroduced into the patient, a process called hematopoietic stem cells transplantation (HSCT). Given time, these stem cells develop into new immune cells therefore reconstructing the patients immune system. At this stage it is possible that mature, faulty, immune cells may be transplanted back into the patient from the original sample. Therefore, before transplantation procedures are carried out to ensure that few mature immune cells are contained within the transplant.

Each of these steps comes with it’s own scientific challenges, not to mention challenges for patients including the hair loss and severe nausea linked with chemotherapy. But, so far, this treatment has also lead to some absolutely amazing success stories with one, previously wheelchair-bound, sufferer regaining the ability to swim and cycle. However, doctors stress that this is a particularly aggressive form of treatment and that it may not be suitable for all MS sufferers.

Dr Emma Gray, head of clinical trials at UK’s MS Society, said: “Ongoing research suggests stem cell treatments such as HSCT could offer hope, and it’s clear that in the cases highlighted by BBCs Panorama they’ve had a life-changing impact. However, trials have found that while HSCT may be able to stabilise or improve disability in some people with MS it may not be effective for all types of the condition.”

Dr Gray said people should be aware it is an “aggressive treatment that comes with significant risks”, but called for more research into HSCT so there could be greater understanding of its safety and long term effectiveness.

Post by: Sarah Fox

![Bottlenose dolphins hesitate and waver when they are uncertain of the correct answer. Image by NASAs [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebrainbank.scienceblog.com/files/2016/01/Screen-Shot-2016-01-11-at-16.41.03-300x228.png)

![Monkeys know when they do not know. Image by Jack Hynes [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebrainbank.scienceblog.com/files/2016/01/Screen-Shot-2016-01-11-at-16.41.11.png)