Few would argue that advancements in science require hard work, long hours and intellectual minds. But a few accidents along the way can certainly help as well. Serendipity, the accidental, but very fruitful, discovery of something other than what you were looking for, has played a significant role in drug discovery through the ages. Here are just three examples to whet your appetite…

Warfarin

Today, warfarin is the main blood thinner (anticoagulant) used in the treatment of blood clotting disorders, heart attacks and strokes. However, its story began on the prairies of North America and Canada during The Great Depression. During the 1920s, financial hardship forced farmers in these areas to feed damp or mouldy hay to their livestock. As a result, many of these seemingly healthy cattle started to die from internal bleeding (haemorrhaging) – an illness later given the name ‘sweet clover disease.’ Although investigators were able to attribute sweet clover disease to the consumption of mouldy hay, the underlying molecule responsible for causing the disease remained a mystery. Consequently, the only potential solutions offered to farmers at the time were to remove the mouldy hay or transfuse the bleeding animals with fresh blood.

Today, warfarin is the main blood thinner (anticoagulant) used in the treatment of blood clotting disorders, heart attacks and strokes. However, its story began on the prairies of North America and Canada during The Great Depression. During the 1920s, financial hardship forced farmers in these areas to feed damp or mouldy hay to their livestock. As a result, many of these seemingly healthy cattle started to die from internal bleeding (haemorrhaging) – an illness later given the name ‘sweet clover disease.’ Although investigators were able to attribute sweet clover disease to the consumption of mouldy hay, the underlying molecule responsible for causing the disease remained a mystery. Consequently, the only potential solutions offered to farmers at the time were to remove the mouldy hay or transfuse the bleeding animals with fresh blood.

It was not until 1939 in the lab of Karl Link that the guilty molecule was isolated – an anticoagulant known as dicoumarol. This is a derivative of the natural molecule coumarin, responsible for the well-recognised smell of freshly cut grass. With the idea of creating a new rat poison designed to kill rodents through internal bleeding, Link’s lab investigated a number of variations of coumarin under the funding of the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). One of these derivatives was found to be particularly effective. Thus in 1948, the rat poison warfarin was born, named after the Body who funded its discovery.

Despite its clear anticoagulating properties, reservations remained about using warfarin clinically in humans. This was until 1951 when a man who had overdosed on warfarin, in an attempt to commit suicide, was successfully given vitamin K to reverse the anticoagulating effects of the rat poison. Hence, with a way to reverse these, the production of a variation of warfarin for human use was developed under the name ‘Coumadin’. This was later successfully used to treat President Dwight Eisenhower when he suffered a heart attack, giving the drug widespread popularity in the treatment of blood clots, which has continued for the last 60 years.

Penicillin

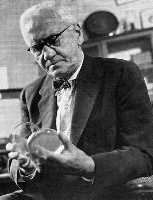

No article on serendipity in drug discovery would be complete without at least mentioning the discovery of the antibiotic penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming. It was 1928 when Fleming returned to his laboratory in the Department of Systematic Bacteriology at St. Mary’s in London after a vacation. The laboratory was in its usual untidy and disordered state. However, while clearing up the used Petri dishes piled above a tray of Lysol, he noticed something odd about some of the Petri dishes which had not come into contact with the cleaning agent. The Petri dishes contained separate colonies of staphylococci, a type of bacteria responsible for a number of infections such as boils, sepsis and pneumonia. There was also a colony of mould near the edge of the dish, around which there were no visible staphylococci or at least only a few small and nearly transparent groups. Following a series of further experiments, Fleming concluded that this mould, which he named ‘penicillin’, was not only able to prevent the growth of staphylococcal bacteria, but also killed this type of bacteria.

No article on serendipity in drug discovery would be complete without at least mentioning the discovery of the antibiotic penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming. It was 1928 when Fleming returned to his laboratory in the Department of Systematic Bacteriology at St. Mary’s in London after a vacation. The laboratory was in its usual untidy and disordered state. However, while clearing up the used Petri dishes piled above a tray of Lysol, he noticed something odd about some of the Petri dishes which had not come into contact with the cleaning agent. The Petri dishes contained separate colonies of staphylococci, a type of bacteria responsible for a number of infections such as boils, sepsis and pneumonia. There was also a colony of mould near the edge of the dish, around which there were no visible staphylococci or at least only a few small and nearly transparent groups. Following a series of further experiments, Fleming concluded that this mould, which he named ‘penicillin’, was not only able to prevent the growth of staphylococcal bacteria, but also killed this type of bacteria.

However, while today the value of penicillin is well recognised, there was little interest in Fleming’s discovery in 1929. In fact, in a presentation of his findings at the Medical Research Club in the February of that year, not a single question was asked. It was only when pathologist Howard Florey from Oxford happened across Fleming’s paper on penicillin that the true clinical significance of the drug was acknowledged. In 1939, along with Ernst B. Chain and Norman Heatley, Florey conducted a series of experiments in which they infected mice with various bacterial strains including staphylococcus aureus. They then treated half the mice with penicillin while leaving the others as controls. While the controls died, the researchers found that penicillin was able to protect the mice against these types of infection. These exciting findings appeared in the Lancet in 1940 and eventually led to the commercial production of the drug for use in humans in the early 1940s in the United States. Since then, an estimated 200 million lives have been saved with the help of this drug.

However, while today the value of penicillin is well recognised, there was little interest in Fleming’s discovery in 1929. In fact, in a presentation of his findings at the Medical Research Club in the February of that year, not a single question was asked. It was only when pathologist Howard Florey from Oxford happened across Fleming’s paper on penicillin that the true clinical significance of the drug was acknowledged. In 1939, along with Ernst B. Chain and Norman Heatley, Florey conducted a series of experiments in which they infected mice with various bacterial strains including staphylococcus aureus. They then treated half the mice with penicillin while leaving the others as controls. While the controls died, the researchers found that penicillin was able to protect the mice against these types of infection. These exciting findings appeared in the Lancet in 1940 and eventually led to the commercial production of the drug for use in humans in the early 1940s in the United States. Since then, an estimated 200 million lives have been saved with the help of this drug.

Viagra

Despite today being widely known for its ability to help men with erectile dysfunction, Viagra was not originally designed for this purpose. The drug company Pfizer had initially hoped to develop a new treatment for angina, one that worked to reverse the constriction of blood vessels that occurs in this condition. However, clinical trials of Viagra, known then as compound UK92480, showed poor efficacy of the drug at treating the symptoms of angina. Nonetheless, it was highly effective in causing the male recipients in the trial to develop and maintain erections.

Upon further investigation, it was identified that, rather than acting to relax the blood vessels supplying the heart, Viagra caused the penile blood vessels to relax. This would lead to increased blood flow to this appendage, resulting in the man developing an erection. Following this unexpected discovery, Pfizer rebranded Viagra as an erectile dysfunction drug and launched it as such in 1998. Today, Viagra is one of the 20 most prescribed drugs in the United States and has, I’m sure, left Pfizer thanking their lucky stars they were involved in its serendipitous discovery.

The accidental discoveries of warfarin, penicillin and Viagra are just three instances of serendipity in drug discovery from a long list – one far longer than can fit in this article. Nevertheless, these cases provide excellent examples of how unplanned factors such as mysterious deaths, unexpected side effects during drug trials, and even just plain untidiness, has led to significant advances in the field of drug discovery. Such serendipitous events have given us a range of indispensable medications which we still rely on today, and I’m sure will continue to provide new and exciting breakthroughs in the future.

Post by: Megan Barrett