What did we know about Ebola before 2014? Fatal. Cruel. Limited to Sub-Saharan Africa.

Last year this all changed.

In 2014 an outbreak in Central Africa gained global media attention. Not only the largest epidemic of the disease to date, so far resulting in over 22,000 suspected cases and nearly 9 000 deaths (WHO report 01/02/2015), it is also the first to impact the Western world. So where do we stand a year into the outbreak?

What is Ebola?

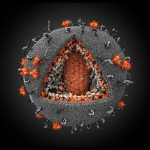

Ebola, first reported in 1976, takes its name from a river near one of the original affected areas. Four different viruses are known to cause the disease humans, after being transmitted by wild animals.. The infection spreads between individuals through direct contact with bodily fluids.

Ebola, first reported in 1976, takes its name from a river near one of the original affected areas. Four different viruses are known to cause the disease humans, after being transmitted by wild animals.. The infection spreads between individuals through direct contact with bodily fluids.

Symptoms can take up to a month to develop – beginning as typical “flu-like” signs (fever, fatigue, muscle pain) before becoming more severe (vomiting, diarrhoea, organ damage, internal/external bleeding). On average 50% of Ebola cases result in death, although the mortality rate can be as high as 90%, depending on the source.

Since being first identified, nearly 20 major outbreaks have been reported. Despite the ruthlessness of the disease, no cure or direct treatment has ever been developed and therapeutic plans tend to focus on supportive measures.

The 2014 Ebola outbreak

Although first reported in late March, in fact it all started in December 2013 with the source a 1 year old boy in Guinea West Africa. A series of misdiagnosis meant it took 4 months for cases to be identified as Ebola.

By this time the virus had taken hold of Africa. Not only had the vicious disease already been suspected to have infected 80 individuals and caused 50 deaths, but cases had by now been reported in other parts of West Africa.

By this time the virus had taken hold of Africa. Not only had the vicious disease already been suspected to have infected 80 individuals and caused 50 deaths, but cases had by now been reported in other parts of West Africa.

The outbreak was by now too large to contain. Within 6 months the disease would spread beyond the continent, as far as Europe and the USA, becoming one of the most talked about global health epidemics of the 21st century.

What has the therapeutic impact of the 2014 Ebola outbreak been?

Late last year the Ebola epidemic was still rife. With the death rate at 70% and no direct treatment available, the World Health Organisation had no other plan except to take the unprecedented step of allowing the use of un-trialled treatments.

Now trials of several novel therapeutic plans are underway or about to commence in West Africa.

Now trials of several novel therapeutic plans are underway or about to commence in West Africa.

Another treatment involves the use of blood/plasma from recovered patients. Known as convalescent plasma therapy, the treatment is quick to develop, easy to implement (even in poor countries), with a potential bank of thousands of Ebola survivors to act as donors.

So while drug development may appear more beneficial for the long-term fight against Ebola, and indeed the effectiveness of several agents is currently being assessed in these areas, blood-based therapies may be more suited for the current outbreak.

Early 2015 also saw the beginning of two separate vaccination trials.

Vaccinations allow the body to build immunity against a specific virus, in this case Ebola. Both newly developed vaccines already passed Phase I clinical trials and have been shown safe for human use. Thus, February this year saw the start of Phase II and Phase III trials in West Africa. It is hoped these trials will determine the safety and effectiveness in a broader infected population and one day the working vaccine will become available internationally on a large-scale.

Controlling the spread of Ebola

One of the main driving factors behind the outbreak last year was the confusion regarding diagnosis. Since Ebola symptoms resemble those of other diseases in Africa, such as malaria and typhoid, Ebola can often be misidentified – especially in areas where cases have never been reported.

One of the main driving factors behind the outbreak last year was the confusion regarding diagnosis. Since Ebola symptoms resemble those of other diseases in Africa, such as malaria and typhoid, Ebola can often be misidentified – especially in areas where cases have never been reported.

To increase the odds of surviving, and limit the spread of the virus, those infected need to be rapidly identified, isolated and begin treatment as soon as possible. Tools which allow this to happen are currently being trialled in the most affected areas of Africa . One such tool involves low-resource kit that can identify the virus within 15 minutes.

Will the 2014 Ebola outbreak see the development of a direct Ebola treatment?

The unusual move of allowing un-trialled treatments creates the perfect opportunity to test the effectiveness of many new potential therapeutic plans quickly in a real-life scenario. However, these trials are not in any means controlled. So sadly even if a therapy is believed to be effective, it will have to go through further trials before it is deemed safe enough for widespread use – a process that can take several years.

In addition, the encouraging news that we have begun to slow transmission and are now in the process of ending the epidemic may have a negative impact on the tests. Already a trial of a potential Ebola drug in Liberia has been stopped because the case numbers have dropped to a level, at which the effectiveness of the drug cannot be clearly confirmed. .

After a year of the mass heartbreak caused by Ebola the seemingly unstoppable disease appears to be finally slowing. Although the trials of the new treatments have created hope for a solution, there is still plenty of work to do before we eradicate Ebola.

Post by: Claire Wilson

References

Ebola Virus Disease. World Health Organisation.

Ebola raises profile of blood-based therapy. Declan Butler, Nature.

Ebola vaccines, therapies and diagnostics.

New 15-minute test for Ebola to be trialled in Guinea. Wellcome Trust.

Wellcome Trust-funded Ebola treatment trial stopped in Liberia.

In 2010, a baby was born prematurely to a mother whose HIV was only discovered during delivery. With no prenatal care, and therefore a high risk of exposure to the virus, the gutsy call was made to begin aggressive treatment with a combination of three antiretroviral drugs at just 30 hours old. Infection was confirmed soon after and the child remained receiving therapy.

In 2010, a baby was born prematurely to a mother whose HIV was only discovered during delivery. With no prenatal care, and therefore a high risk of exposure to the virus, the gutsy call was made to begin aggressive treatment with a combination of three antiretroviral drugs at just 30 hours old. Infection was confirmed soon after and the child remained receiving therapy.