Have you ever thought about being a scientist? The growing movement of citizen science encourages public volunteers to contribute towards ‘the doing’ of scientific research, all without giving up the day job, undergoing extensive training or putting on a white coat. Topics and activities involved can vary widely, but typically ‘citizen scientists’ get involved in collecting, processing and/or interpreting data in some way, all under the direction of professional scientists or researchers. For example, you could be asked to record observations about the natural environment, track human or animal behaviours, perform logging or mapping activities, or interpret images and patterns.

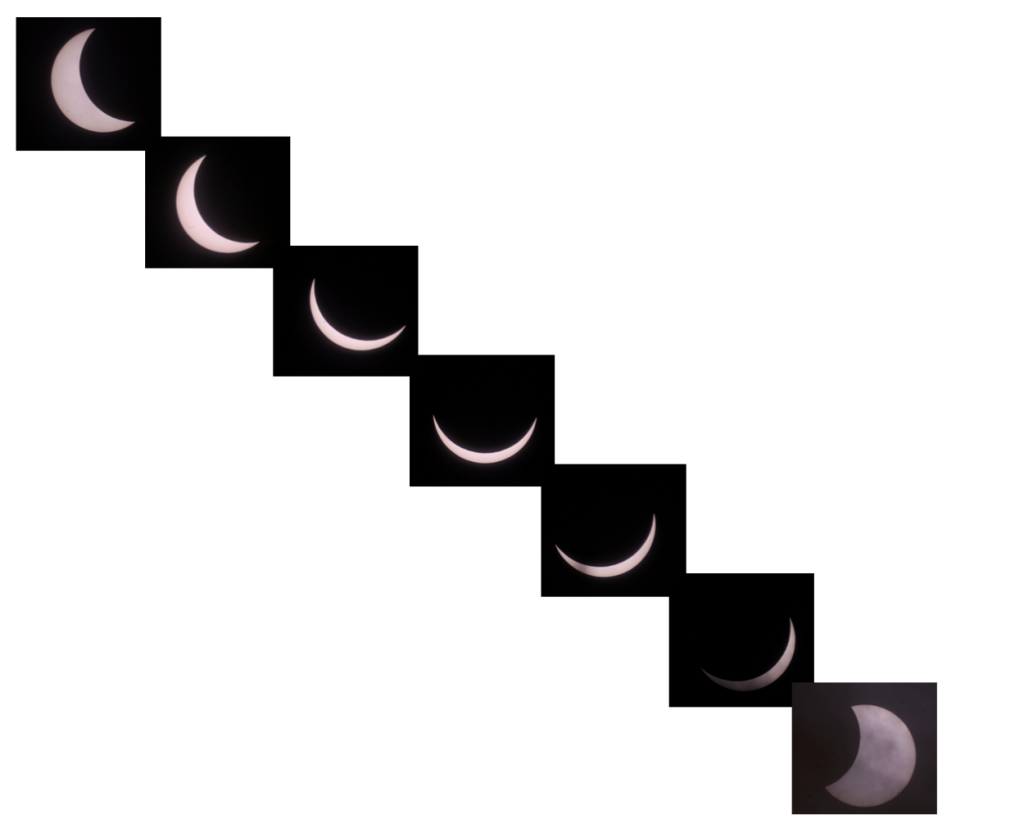

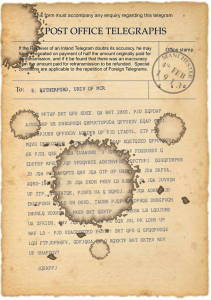

Galazy Zoo (a study to investigate the properties and histories of galaxies) is regarded as one of the most well-known and successful citizen science projects. Launched in 2007, the project started life as a website that invited members of the public to sort images of galaxies into different categories (ellipticals, mergers and spirals). Stunned by the speed and scale of the initial response (over 70,000 classifications received within 24 hours), the project has continued to attract an army of willing volunteers who perform ever more skilled tasks. Furthermore, they have developed a growing number of online resources to engage schools and the general public in astronomy. Meanwhile, in Old Weather, volunteers delve into and transcribe the contents of historical logbooks from ships. Transcribing handwritten entries about weather readings taken at sea from thousands of logbooks into a digital (and analysable) format would clearly be a mammoth, and potentially impossible, task; yet, opening it up to the public has made it feasible.

So, citizen science can be a valuable way of both advancing scientific inquiry and engaging the public in science. The general public can indulge their own interests whilst getting the feel-good factor of knowing they’ve contributed towards science. Basically, it’s a win-win situation. Or is it? Cynics may argue that some projects are little more than crowdsourcing, enabling scientists to achieve what would otherwise be too expensive, time consuming or intensive for researchers working alone. Whilst it’s true that there may be pragmatic reasons for using citizen science approaches, projects can offer opportunities for genuine dialogue and collaboration between scientists and the public. For example, members of the public with hay fever are now involved in designing #BritainBreathing, a citizen science project aimed at understanding more about seasonal allergies such as hay fever. So far, individuals have been involved in ‘paper prototyping’ workshops, to sketch out the design of a mobile phone app that will capture data about allergy-related symptoms such as sneezing, breathing and wheezing. Hence, the goal is to engage citizens in multiple roles whereby they can act as co-designers and collaborators, and not just as passive sensors.

Citizen science is not a new concept. Indeed, the first project has been traced back to 1833, when the astronomer Denison Olmsted invited the public to submit first-hand accounts of a spectacular meteor shower. Nonetheless, the term ‘citizen science’ only entered the Oxford English Dictionary In 2014 and it is enjoying a ‘boom period’ at the moment, with an explosion of projects emerging. Why the sudden popularity, you might ask? Two factors stand out. First, advances in information technology and the widespread availability of internet-enabled devices (e.g. smartphones and tablets) have enabled individuals to contribute data online in real-time, on the move, and with minimal effort. Second, there is growing recognition that the public have a stake in science and that research should be more democratic, shaped by the interests and needs of the people. Whilst the former is certainly useful in enabling projects, personally it is the latter that most excites me. Citizens have more opportunities (and power) than ever to shape research to generate the knowledge and solutions we want for our futures. So go on, indulge your inner scientist. Power to the people.

Guest post by: Lamiece Hassan

Lamiece is a health services researcher and public involvement specialist at The University of Manchester. With a background in psychology, her research has explored topics such as health promotion, mental health in prisons and psychotropic medicines. Her current work focuses on how we can use digital technologies and health data in trustworthy ways to empower patients and improve health.

Lamiece is a health services researcher and public involvement specialist at The University of Manchester. With a background in psychology, her research has explored topics such as health promotion, mental health in prisons and psychotropic medicines. Her current work focuses on how we can use digital technologies and health data in trustworthy ways to empower patients and improve health.