At the start of February we heard the horrible news that Philip Seymour Hoffman, a wonderful Academy Award winning actor, had died from a drug overdose. This followed news from last year of the death of Glee star Cory Monteith from a heroin and alcohol overdose. Perhaps the most shocking thing about these deaths was that no-one saw them coming.

Worryingly, the reality is that drug relapses such as these are all too common, but often go unnoticed. Our understanding of the science behind these relapses has come on leaps and bounds in recent years. We have moved from understanding how a drug makes us feel pleasure, to understanding how a drug may cause addiction and subsequent relapse.

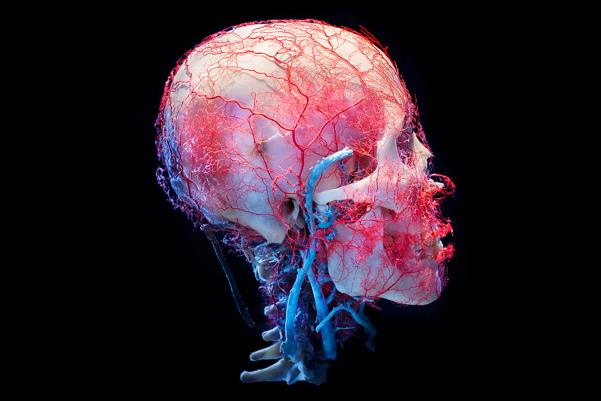

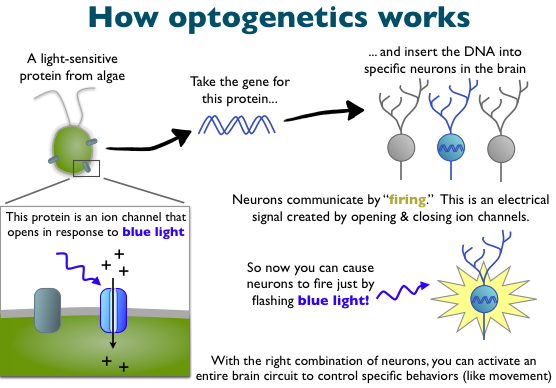

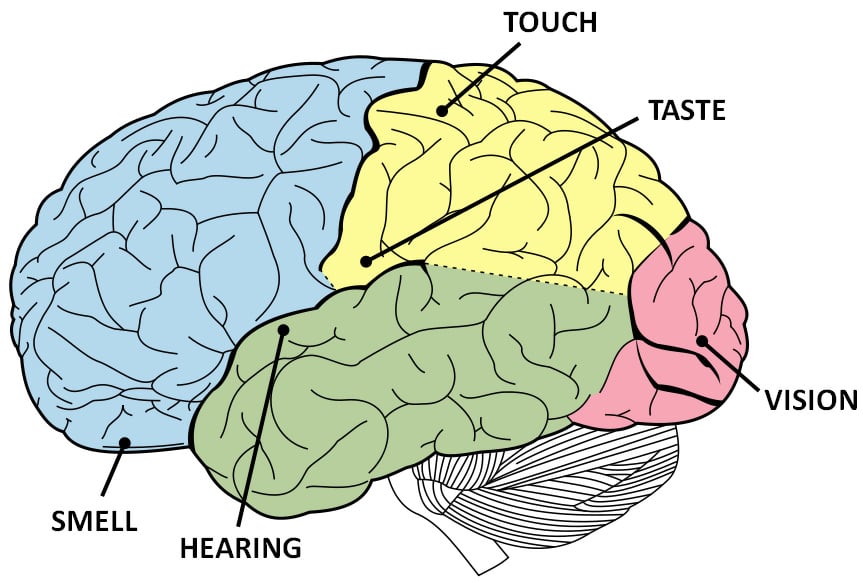

Classically, scientists have explained addiction by focusing on how a drug affects the reward systems of the brain. Drugs have the ability to make us feel good due to their actions on this pathway. The reward system of the brain is a circuit that uses the chemical dopamine to stimulate feelings of elation and euphoria. This system has a motivational role and normally encourages survival behaviours such as obtaining food, water and sex. Drugs of addiction can hijack this system to induce euphoric feelings of their own.

Cocaine, for example, is a highly addictive drug that blocks reuptake transporters of dopamine. These transporters normally soak up excess dopamine and ensure that the reward system is not overactive. Cocaine stimulates euphoria by preventing dopamine from being retrieved and increases stimulation of the reward system. Another addictive drug, nicotine directly stimulates the reward system to produce more dopamine.

These classical views work well when considering the motivation to start taking drugs and to continue taking drugs in the initial stages. The drug stimulates feelings of euphoria, ‘rewarding’ the taker. The taker learns to associate taking the drug with these feelings of euphoria and therefore the taker wants to do it more.

This theory can also explain some aspects of withdrawal. Just as activation of the reward system has a physiological role, so does shutting it down. It appears there is such a thing as ‘too much fun’. If we spent all of our time copulating and over-eating we’d be prime targets for predators. Due to this, the body has its own off-switches in our reward pathways that try to limit the amount of pleasure we feel. These normally work by desensitising the brain to dopamine, so that dopamine isn’t able to produce the effects it once could.

During drug use, when dopamine levels and subsequent pleasurable feelings are sky-high, the brain works to limit the effects of this overload of dopamine. When the drug wears off, dopamine levels fall but the desensitisation to dopamine persists. This causes withdrawal, whereby when there are no drugs to boost dopamine, one fails to gain pleasure from previous pleasurable day-to-day activities. The dopamine released when one has a nice meal for example, is no longer sufficient to cause enough activity in the reward pathways and no satisfaction is felt.

Scientists believed for a while that the reward system could tell us all we need to know about addiction and how it manifests itself throughout the brain. However, tolerance builds and the euphoric responses to these drugs begin to wane. Some users start feeling dysphoria, a horrible sombre feeling, and don’t know why they continue using these drugs as they are no longer experiencing euphoria – the reason why they took the drug in the first place.

On top of that, when doctors and therapists talk to drug addicts who relapse, the addicts often do not talk about wanting to feel pleasure, wanting to feel elation again. They talk of stress building up inside them, the release from this stress they want to feel.

When asked about why they relapsed, previously clean addicts often talk of stressful events leading to their relapse – they lost their job or they broke up with their partner. First-hand accounts suggest this stress seems to be the driver of a relapse, the driver to continued addiction.

This is depicted clearly back in the 19th century by the eccentric American author and poet Edgar Allan Poe:

“I have absolutely no pleasure in the stimulants in which I sometimes so madly indulge. It has not been in the pursuit of pleasure that I have periled life and reputation and reason. It has been the desperate attempt to escape from torturing memories, from a sense of insupportable loneliness and a dread of some strange impending doom.”

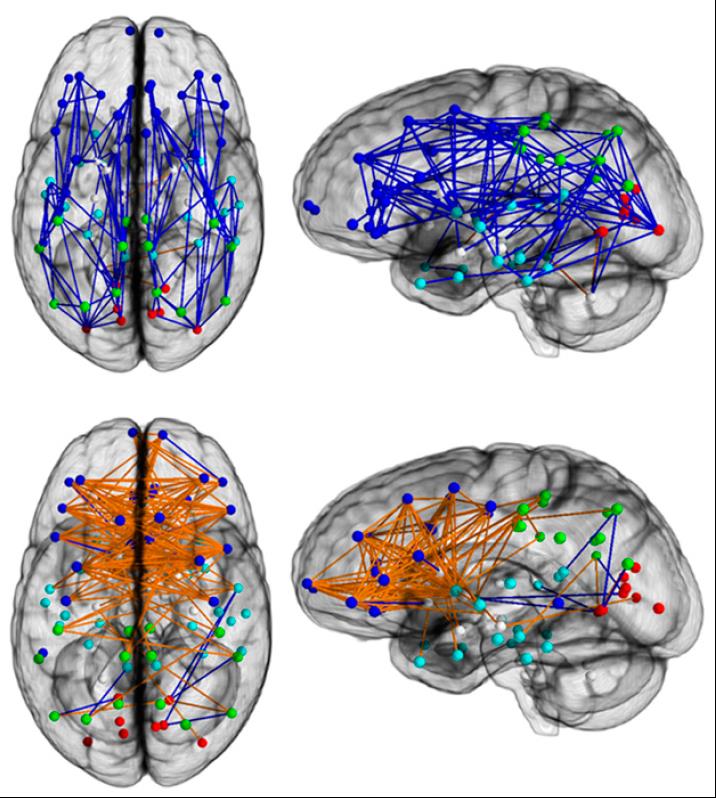

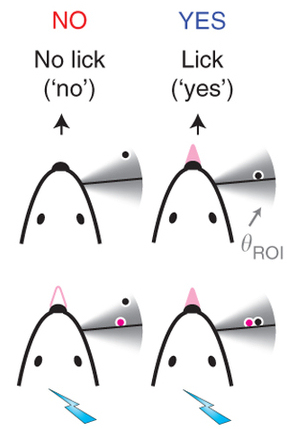

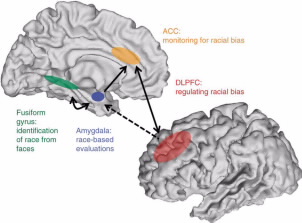

Intrigued by this, scientists have now found many threads of evidence to suggest that stress pathways within the brain play a key role in addiction and relapse. For example, work into this so-called ‘anti-reward system’, has led to proof that stress can instigate drug-seeking behaviours in animal studies.

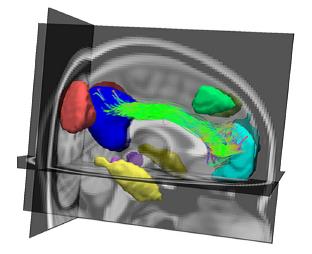

Our stress pathways are built around a hormone system known as the HPA axis – the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This axis is responsible for regulation of many biological processes but plays a crucial role in stress.

CRF = corticotrophin releasing factor; ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone

Much like other drugs of addiction, drinking alcohol feels good due to its actions on the reward system. In line with addicts of other drugs, alcoholics commonly talk about the release of stress they want to feel. Evidence is building to suggest that alcoholics have increased activity through the HPA axis.

A hormone called cortisol is the final chemical involved in the HPA axis, released from the adrenal glands during times of stress. Compared to occasional drinkers, alcoholics have higher basal levels of cortisol and a higher basal heart rate – two common measures of HPA activity. This pattern has also been seen in other addictions. For example, in previously clean cocaine addicts, higher basal HPA axis activity correlates with an earlier relapse and higher levels of stress hormones (e.g. cortisol) can predict a higher usage of cocaine in the future.

A puzzling scenario surrounding addiction is how most users can enjoy occasional usage but for some, this can spiral uncontrollably into an addiction? The likelihood of different individuals having a higher propensity to addiction could well be explained by differences in how different people respond to stress.

So what begins as a behaviour driven by the reward pathways appears to have now escalated into a behaviour dominated by stress pathways. It seems it is the stress that drives the craving and relapse, not the longing for a ‘reward’.

Armed with this knowledge, work into how we can design medicines to alleviate cravings and prevent relapse has shown early potential. Blocking the first stage of the HPA axis has been able to prevent alcohol addiction in rats. Blocking a suspected link between the stress pathways and the reward pathways has shown to be able to prevent stress-induced cocaine seeking behaviour.

These compounds have yet to be tested in humans but the early promise is there. It is an intriguing theory that the susceptibility to stress of different individuals may explain the varying susceptibility to addiction. This idea provides a basis for further work to try to understand why some individuals can only occasionally use, whilst others become addicted. Relapse is a horribly common situation amongst drug addicts and with the stigma attached giving addicts substantial additional stress, it is well-worth the research to prevent more unnecessary deaths. Unfortunately, this will be too late for those we have already lost, but the future is bright with continued progress in understanding these horrible ordeals.

By Oliver Freeman @ojfreeman