Huntington’s is a devastating genetic disease, described by patients as being like “Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and motor neurone disease rolled into one”. In most cases the disorder can be traced back to an inherited genetic mutation which increases the length of the Huntingtin gene. The mutated gene harbours an abnormally long sequence of the DNA base pairs C A and G (this type of mutation is known as a CAG expansion). Sufferers commonly have one normal copy of the Huntingtin gene and one mutant copy and, over time, mutant Huntingtin protein builds up in the brain, damaging neurons and ultimately leading to the devastating symptoms of the disease.

A recent wave of articles (here, here, here) suggest that scientists may be on the cusp of a groundbreaking leap in treating this disorder; giving sufferers hope that a new drug could soon stop the march of Huntington’s in its tracks.

This drug has been named Ionis-HTTRx and, despite its dull moniker, it represents a pretty spectacular breakthrough in the field of Gene silencing.

But what is Gene silencing and what does this drug actually do?

Genes are segments of DNA which contain the instructions for making different proteins. These proteins perform a huge range of essential functions in our bodies; from signalling between cells, speeding up biological reactions to forming structural support for our cells.

So, to understand Gene silencing, we first need to understand the journey from Gene to protein.

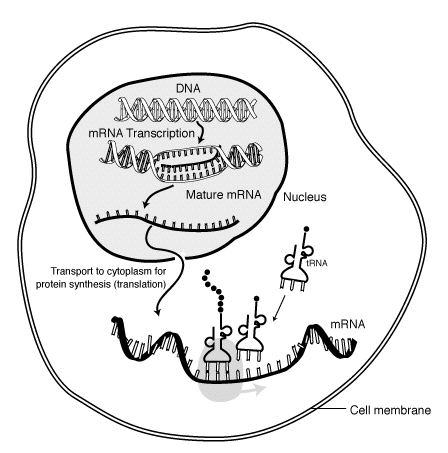

Genes sit nestled within the tight curls of the DNA double helix. Specialised molecular machinery within the cell’s nucleus can break open the DNA helix and read individual Genes, creating an almost identical, single sided copy of the Gene known as mRNA. You could think of DNA as a hybrid between a ladder and a spiral staircase, while mRNA looks a bit like a small segment of that ladder which has been split down the middle. It is this mRNA which can slip outside the cell’s nucleus and act as a template for the creation of a protein (through a process known as transcription).

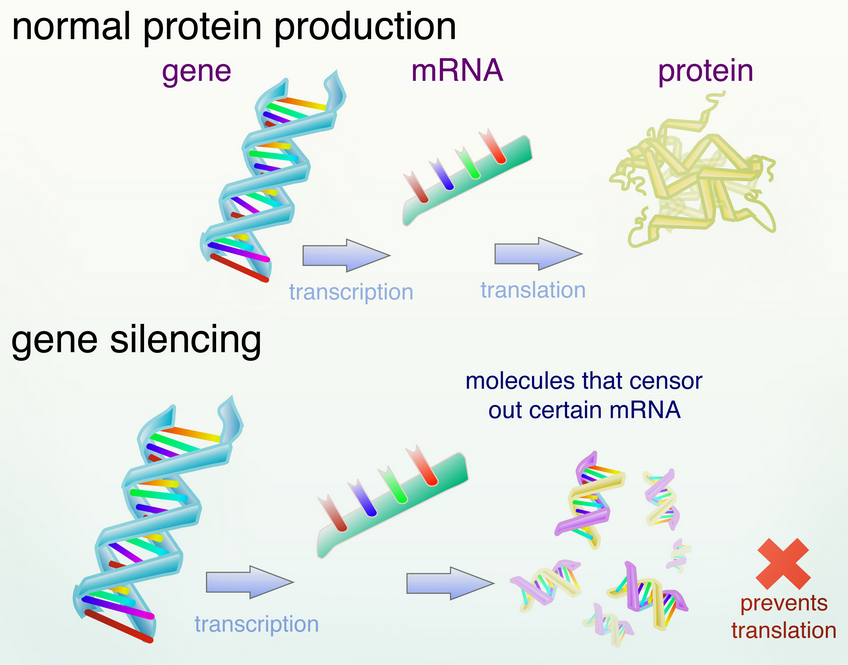

How can this process be silenced?

Gene silencing targets mRNA. Scientists have designed molecules which recognise the mRNA produced by specific genes, home in on these strands and stop them from being transcribed into proteins. This means that researchers can target specific proteins and selectively reduce the amount produced in cells.

Ionis-HTTRx is a antisense oligonucleotide which looks a bit like a mirror image of the huntingtin mRNA and, due to its structural similarity to the mRNA, it binds to the huntingtin mRNA stopping the transcription process – therefore silencing the gene’s effect.

Back in 2012 studies in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease found that when this drug was administered directly into the animal’s spinal fluid, mice showed a delay in disease progression and ‘sustained disease reversal’. While the most recent study involving 46 men and women in the early stages of Huntington’s found that 4 spinal injections, each one month apart, lead to a significant drop in the amount of harmful huntingtin protein present in spinal fluid samples. The trial did not last long enough to uncover whether this drop in harmful protein would ultimately translate into a reduction of clinical symptoms but a second trial, aimed at answering this question, is definitely on the cards.

Not only is this discovery exciting for those harbouring the huntingtin mutation, some suggest that the theory behind this treatment could be extrapolated to other conditions – namely Alzheimer’s disease. Our current understanding of Alzheimer’s disease suggests that it is also caused by misbehaving proteins. However, since the genetic causes of Alzheimer’s are more complex and less well understood than those underlying Huntington’s it is yet to be seen whether similar therapies would prove effective in this case.

Post by: Sarah Fox

However, as part of my interest in health apps, I downloaded the NHS’s

However, as part of my interest in health apps, I downloaded the NHS’s  For me, playing with this app has been amazingly interesting. Although the information the app gives you is no different from what you could read yourself on an ingredients list, the app interface gives you a quick and easy way to gauge, in a comparative way, how healthy each product really is. It also offers tips for healthier alternatives and recipes which has given me something extra to think about during my weekly shop.

For me, playing with this app has been amazingly interesting. Although the information the app gives you is no different from what you could read yourself on an ingredients list, the app interface gives you a quick and easy way to gauge, in a comparative way, how healthy each product really is. It also offers tips for healthier alternatives and recipes which has given me something extra to think about during my weekly shop.

Our small group of

Our small group of

In the 1970’s

In the 1970’s  It has been suggested that the key to Christmas spirit may be familiarity and a sense of nostalgia for times long gone. Indeed, what gets the festive juices flowing more than cheesy Christmas movies, twinkling lights and festive family gatherings – experiences we most likely all share and repeat year after year.

It has been suggested that the key to Christmas spirit may be familiarity and a sense of nostalgia for times long gone. Indeed, what gets the festive juices flowing more than cheesy Christmas movies, twinkling lights and festive family gatherings – experiences we most likely all share and repeat year after year.

As the last leaves fall from our trees and the outside world beds down for winter, we at the Brain Bank are turning our thoughts to the UK’s wild critters braving this cruel and often unpredictable season.

As the last leaves fall from our trees and the outside world beds down for winter, we at the Brain Bank are turning our thoughts to the UK’s wild critters braving this cruel and often unpredictable season.

A fun, if slightly unusual Christmas activity, would be to make yourself a solitary bee house. With bee numbers dwindling, it’s never been more important for us to take care of these hard working pollinators, this includes providing them with safe winter accommodation. Bee houses can be bought from your local garden center and hung somewhere warm and dry, however it’s also great fun to make one of these yourself. I recently ran a small event at a local botanical garden where we taught youngsters to make their own bee homes. The activity only took 15 minutes, was relatively cheep and of course the kids all enjoyed getting a bit messy – I’m pretty sure the local bee population were quite pleased with the results too! Instructions for two types of homemade bee houses can be found

A fun, if slightly unusual Christmas activity, would be to make yourself a solitary bee house. With bee numbers dwindling, it’s never been more important for us to take care of these hard working pollinators, this includes providing them with safe winter accommodation. Bee houses can be bought from your local garden center and hung somewhere warm and dry, however it’s also great fun to make one of these yourself. I recently ran a small event at a local botanical garden where we taught youngsters to make their own bee homes. The activity only took 15 minutes, was relatively cheep and of course the kids all enjoyed getting a bit messy – I’m pretty sure the local bee population were quite pleased with the results too! Instructions for two types of homemade bee houses can be found

Much of what we know about Alzheimer’s disease in the human brain comes from postmortem studies. This means that most of our knowledge is skewed towards late stages of the disease. We know that, in these late stages, patient’s brains are severely shrunken and littered with clusters of abnormal proteins known as amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Many academics acknowledge that if we want to successfully treat AD it’s important that we understand what causes these proteins to misbehave in the first place. This is where scientists picked up on an important link between RA and AD.

Much of what we know about Alzheimer’s disease in the human brain comes from postmortem studies. This means that most of our knowledge is skewed towards late stages of the disease. We know that, in these late stages, patient’s brains are severely shrunken and littered with clusters of abnormal proteins known as amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Many academics acknowledge that if we want to successfully treat AD it’s important that we understand what causes these proteins to misbehave in the first place. This is where scientists picked up on an important link between RA and AD.